Here's What Made 'Adventure Time' So Special

Tonight, the last episodes of "Adventure Time" air on Cartoon Network, and -- subsequently -- one of the most audacious, influential (and, ultimately, successful) animated series in modern television will come to a close after nearly a decade. (The short on which the series was based was created back in 2007.)

It's a testament to the all-ages appeal of the show, created by CalArts graduate Pen Ward (who, for the sake of transparency, it should be noted is a childhood friend), that its conclusion feels like some kind of joyous memorial -- it's sad, sure, but it's also an opportunity for fans to openly discuss how much the show meant to them, what their favorite moments were, and how excited they are to pass that love on to an entirely new generation.

In short, "Adventure Time," will be deeply missed.

And its omnipresence, peeking out of shops at the mall and rerunning, almost continuously, on cable and streaming services (it ran for a whopping 279 11-minute episodes), has desensitized us to how different "Adventure Time" was when it first aired in 2010 and what a profound impact it had on animation (and beyond).

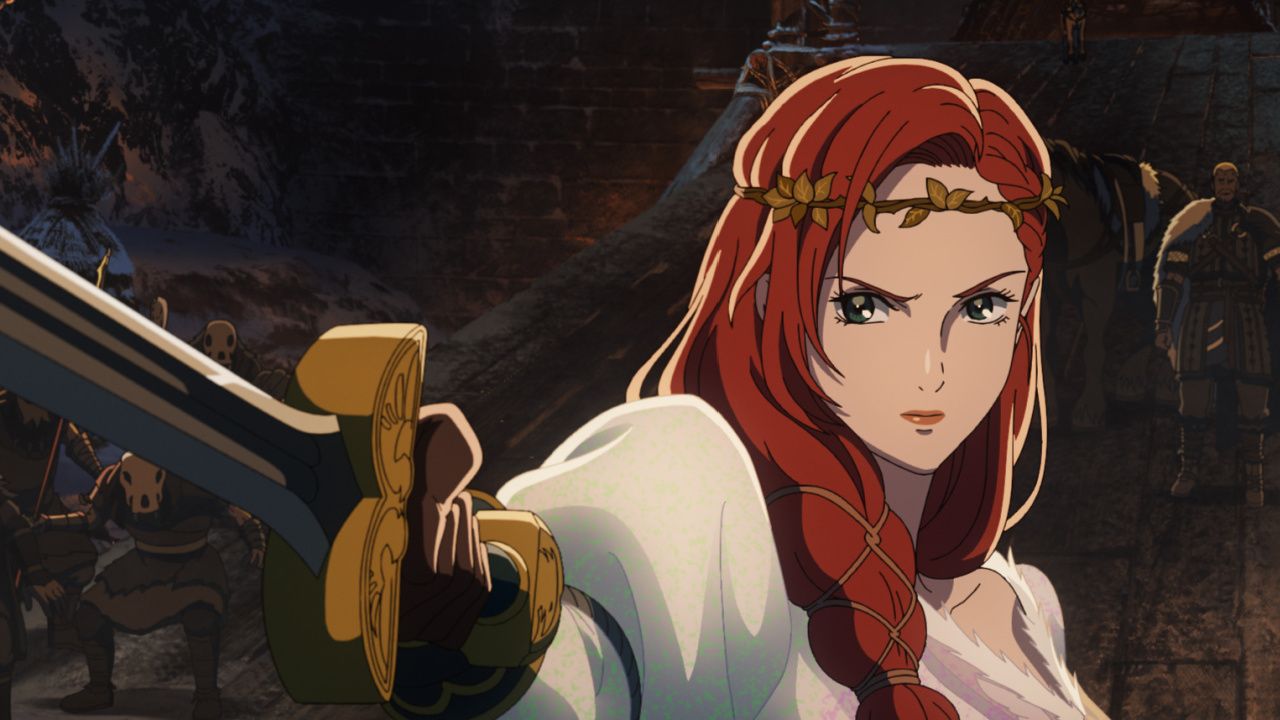

If you've never seen "Adventure Time," it's the story of Finn (Jeremy Shada) and his dog pal, Jake (John DiMaggio), and their adventures in the mystical land of Ooo. They get into adventures and rescue princesses (and are oftentimes rescued by princesses) and form bonds with all sorts of magical characters and creatures. It's a world that is both intricate and sprawling, a kind of fantastical, Miyazaki-influenced world that features almost improvisational dialogue that wouldn't be out of place in one of Richard Linklater's films. It walks a precarious land between the fantastical and the commonplace, and it's totally brilliant at straddling both tone and content.

As the show has gone on, the mythology of the land and characters has depended (whole books have been written about the minutia, apropos of something that obviously owes a considerable debt to the nerdy Dungeons & Dragons); characters back stories have been fleshed out, and whole worlds have been explained.

But none of this has any actually bearing on the show; you could pop an episode on (any one) and still be enamored with the gorgeously stylized characters and colorful artwork. The short running time of the shows allows for this information to be doled out economically; it's only when looking at it as a whole that you can appreciate how staggering it all is.

It's also been hugely influential. Look no further than animation breakthroughs like "Gravity Falls" (created by Alex Hirsch, a CalArts classmate), with its highly-serialized storytelling, or "Over the Garden Wall," a beautiful benchmark miniseries created by "Adventure Time" creative principle Patrick McHale (Ward co-wrote one of the installments). The success of "Adventure Time" proved that children's television could tell grand, finely mechanized stories and others took that knowledge and ran with it.

And it's not just how these stories were told that proved instrumental in the medium, since the animation style has had a weighty effect on the way animation has looked in the near-decade that "Adventure Time" has been on the air. That kind of gentle surrealism, with obvious nods to Japanese animation, has become a staple in other animated shows.

Look at the equally brilliant "Steven Universe" (created by Rebecca Sugar, a former "Adventure Time" staffer) or "Star vs. the Forces of Evil" (created by Ward's classmate, Daron Nefcy) and you'll see all the hallmarks developed on "Adventure Time" -- strong lines, characters with exaggerated features that belie quickly identifiable emotions, and worlds that place the otherworldly snugly beside the everyday.

Maybe what the show will most be remembered for, even though it hasn't been given nearly enough attention, is in its advancement of LGBTQ themes and relationships in children's programming. There is much gender fluidity in the series, particularly when it comes to adorable little computer/video game BMO (who has been referred to in both gendered pronouns) and because Finn and Jake have gender-swapped alter egos.

In one episode, gay ghosts appear. And in a more telling situation, principle characters Princess Bubblegum and Marceline the Vampire Queen, have shared an implied romantic relationship. This reached a head towards the end of last year, when Marceline sang a song about romantic yearning that was clearly aimed towards Princess Bubblegum (staunchly straight loudmouths on Twitter were not fans).

As Moviefone contributor Nick Romano wrote on EW.com, there is a wave of LGBTQ characters in children's entertainment, with many of them coming from creators that worked with Ward in the past, and all of them coming after the strides "Adventure Time" had made. (This has led to "Adventure Time" being heavily censored in some foreign territories.) Many LGBTQ writers have noted how "camp" the "Adventure Time" sensibilities are, and since that kind of vibe has been endlessly replicated and absorbed in the past eight years, you can feel, ever-so-slightly, the entire landscape of children's television animation getting a little bit gayer, one delicious piece of kitsch at a time.

And as much as all of this matters, we'll miss "Adventure Time" for its charming characters, its witty wordplay, its candy-colored (sometimes literally) vistas, its sharp bursts of dark-and-scary, and the way it wound all of this stuff (bold stylization, political progressiveness, odd tonal shifts) into a single, cohesive package that was not only lovable but widely accepted. Ward and his cohorts showed the world something different (really different) and asked for a hug.

And, somewhat miraculously, the world hugged back.