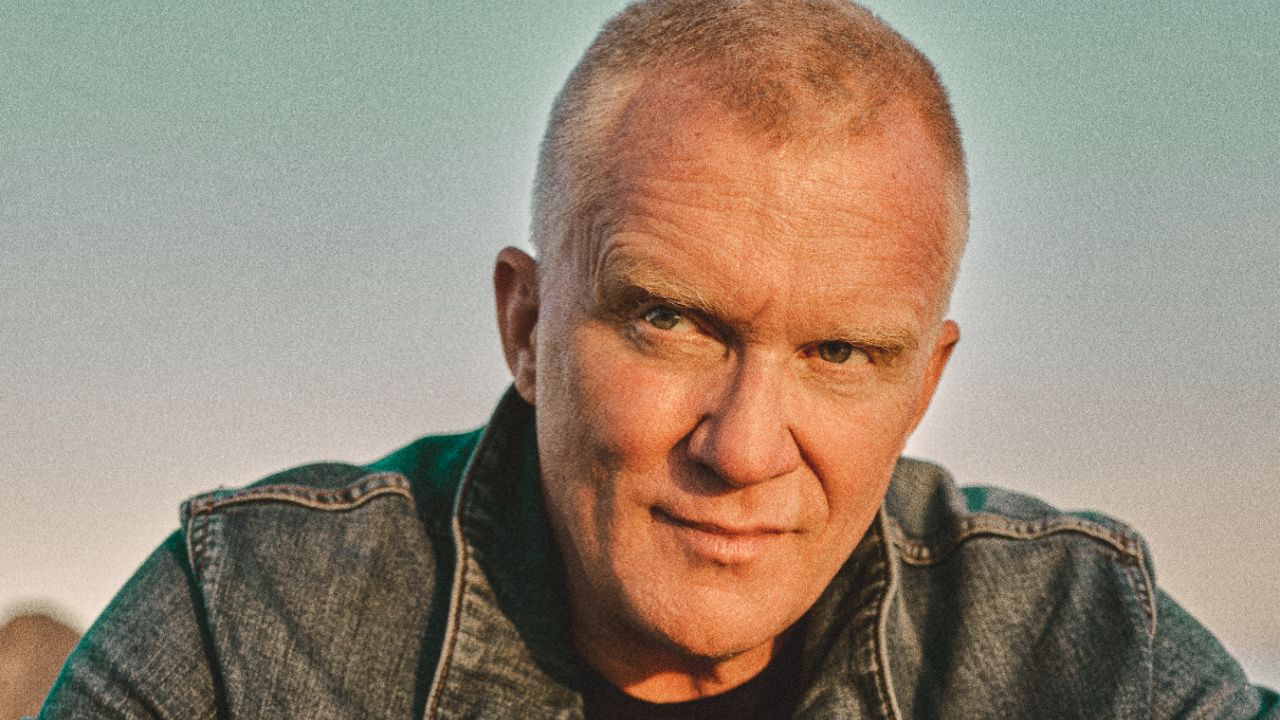

Filmmaker Nicolas Roeg Dead at Age 90

Nicolas Roeg was the type of filmmaker who inspired obsession. His films were experimental and bold, but always had an internal logic, each bit fabricated lovingly and with a nearly forensic attention to detail. He took big risks (often when it came to who he cast in his films) and often broke new ground, all in the name of creating singular works of art that people would happily obsess over. And while Roeg died today at the age of 90, he left behind a body of work that felt unique and personal, especially in the pantheon of modern filmmakers. Each film felt handcrafted and singular; all the better to obsess over.

Even if you don’t know Roeg’s work, chances are you’re aware of him. He began his career as a cinematographer and second-unit director, working for David Lean on such beloved epics as “Doctor Zhivago” and “Lawrence of Arabia,” and as a cinematographer on Roger Corman’s “Masque of the Red Death,” Francois Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451” and Richard Lester’s “Petulia.” 1970 saw the release of “Performance,” a film Roeg co-directed with Donald Cammell and which shares many of the defining characteristics of Roeg’s oeuvre, including his decision to cast a rock star in a lead role (this time it was Mick Jagger, who also contributed to the original score) and a loose, fractured structure that reveals itself the more times you watch it.

The year after “Performance,” Roeg released one of his masterpieces – “Walkabout,” the story of a pair of British children who are left to roam the harsh Australian outback after their tony father commits suicide. The movie seems shocking today, from the full-frontal nudity of the young stars to the harshness of the suicide (the father first tries to kill the kids, before turning the gun on himself) to the tenderness with which Roeg portrays native aboriginal Australians. It’s a bona-fide masterwork and heralded Roeg as a major force not only in British cinema but on a global scale. After a little-seen documentary on the Glastonbury music festival, he released “Don’t Look Now” in 1973, a supernatural thriller based on a story by Daphne Du Maurier (the author that wrote the stories that would eventually become Hitchcock classics “Rebecca” and “The Birds”) that co-starred Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as a young couple mourning the death of their child in Venice. (Sutherland adored the director and named one of his sons Roeg.) “Don’t Look Now” is now considered a classic, one of the scariest movies of all time, and one of the most influential. And not just because the sex scene, often cited as one of the most erotic in film history, was reportedly not simulated.

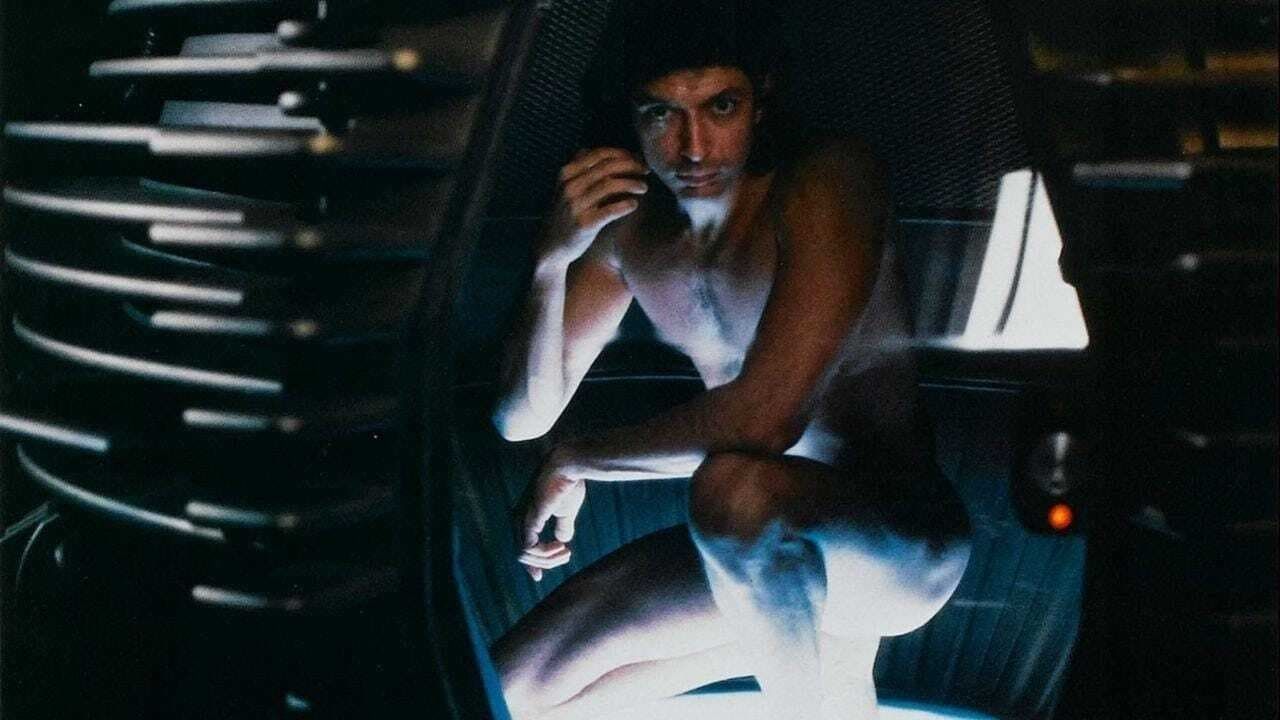

Three years after “Don’t Look Now,” Roeg teamed up with another rock star for “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” casting David Bowie as a marooned alien creature on a cold and indifferent earth. A surreal masterpiece every bit as powerful as “Walkabout” or “Don’t Look Now,” it heralded Bowie as a major acting force and has proven an influential pop culture artifact whose echoes you can still feel today (there was even a direct reference to the movie’s iconic wallpaper in Zack Snyder’s “Watchmen”). After “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” Roeg worked with yet another musician-turned-actor in Art Garfunkel for “Bad Timing.” A kinky, surrealistic thriller, the movie was awarded an X-rating in the United States for its sexual frankness. Garfunkel’s performance is iffier than either Jagger or Bowie’s, but it feels like an intensely personal, painful piece of work (his girlfriend at the time committed suicide during production) and the movie remains one of his more underrated efforts.

In the years that followed, Roeg’s output would be just as interesting but less widely heralded, with his more notable works being “Eureka” (1983), which has a terrific cast, anchored by Gene Hackman as a greedy oilman, and “Insignificance” (1985), a theatrical chamber piece that imagines an encounter between Marilyn Monroe, Joseph McCarthy, Albert Einstein, and Joe DiMaggio. Even something as straightforward as those concepts becomes warped, fractured, and altogether unique in Roeg’s hands. (He also directed a terrific segment of 1987’s musical anthology “Aria.”) His last truly fascinating piece being 1990’s “The Witches,” which marked a terrific adaptation of British author Roald Dahl’s children’s book of the same name. It was criticized for being too scary which, of course, meant that it adapted Dahl brilliantly, and was one of the last movies Jim Henson ever worked on. Like most of Roeg’s films, its reputation has only strengthened over the years, with many rightfully acknowledging it as an ahead-of-its-time classic.

In Roeg’s later career, he worked mostly in television (including an episode of “The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles”) and in marginally released oddities (like 2007’s bizarre-in-a-bad-way “Puffball,” which saw him reunite with Sutherland). But his influence and standing could never be diminished, with a number of modern filmmakers citing him as a premiere influence, among them Steven Soderbergh (who based the sex scene in “Out of Sight” on “Don’t Look Now”), Edgar Wright (who payed homage to the director in “Hot Fuzz”), Christopher Nolan (whose nonlinear editing style owes a huge debt to Roeg), Danny Boyle (ditto) and Guillermo del Toro (who spent the morning re-tweeting eulogies to the director and who often discussed remaking “The Witches”).

If you’ve never seen one of Roeg’s movies, well, I envy you. Watching “Don’t Look Now” or “Walkabout” for the first time is like having a filmmaker speak directly to you, like you’ve been instantly inducted in a club exclusively for people who like the coolest, most creative stuff imaginable. Roeg was a filmmaker who shot to popularity early in his career and never stopped experimenting with craft and form, even after people stopped paying attention. He will be missed, he will be cherished, and he will be obsessed over, as long as there is cinema.