'Green Book' Review: This Flawed, Feel-Good Oscar Hopeful Has Its Charms

Every time I see a movie like “Green Book,” I wonder how many more stories about overcoming racism Hollywood needs to tell. And then I glance at the news and realize it’s apparently a lesson that audiences keep needing to learn.

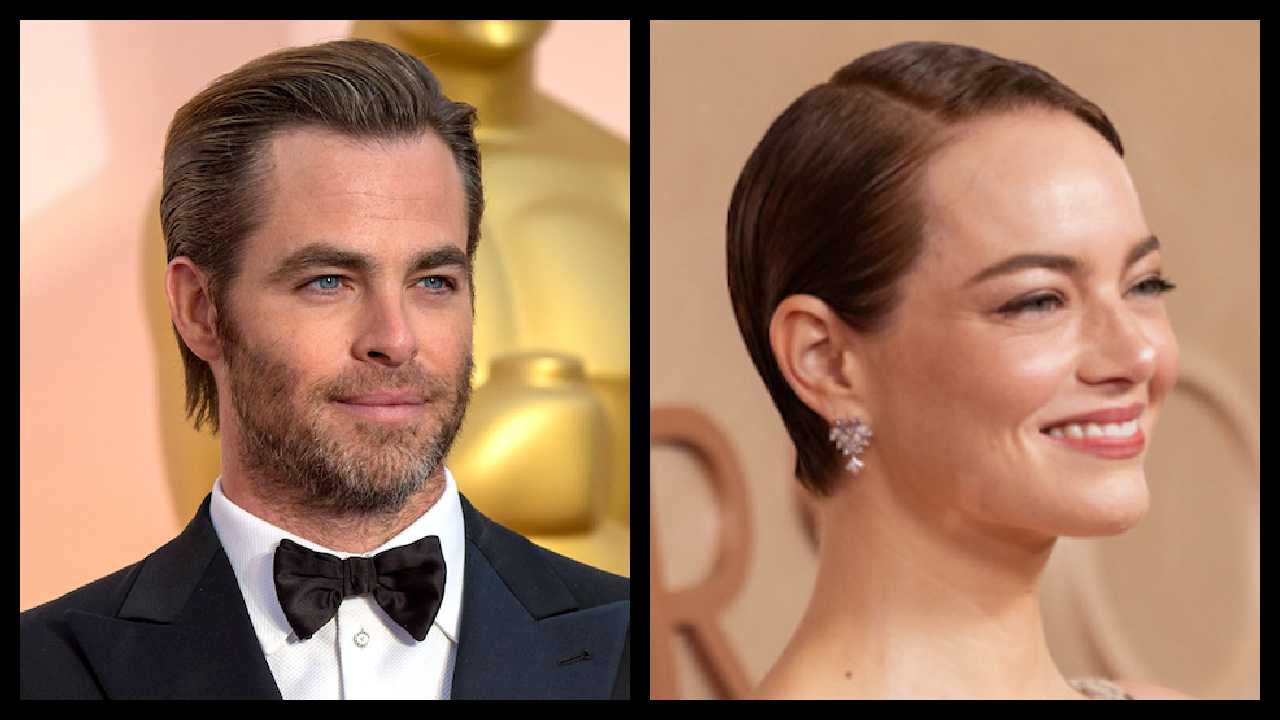

Directed by Peter Farrelly -- one half of the gentlemen responsible for “Dumb and Dumber" and “There’s Something About Mary") -- he indulges in the duo’s proclivity for road movies but otherwise restrains himself from turning the true story of a Jamaican classical pianist being driven through the 1960s Deep South by a foul-mouthed Italian bouncer into an unsuitably raunchy, lowest-common-denominator comedy. Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen, as passenger and driver, respectively, form an occasionally discordant but ultimately satisfying pair as their characters’ real-life adventure offers a canny reversal of many of the tropes of movies about learning to see past skin color.

Mortensen plays Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga, a doorman and bouncer who finds himself out of a job when the Copacabana closes for repairs. While scrounging for cash by challenging neighborhood heavyweights to eating contests, he receives an unexpected job offer from Dr. Don Shirley (Ali), a black pianist who needs a driver and valet to shepherd him through the Deep South for a tour with his trio.

Frank’s insular life in New York -- in the same neighborhood his parents lived in before him, and his children would after him -- fails to prepare him for the opposition Dr. Shirley faces in towns where the musician cannot eat or use the bathroom in the same venue he is scheduled to perform. Nevertheless, he quickly proves valuable as an enforcer and one-man security team when Shirley, isolated in a different way from not just his band mates or the locals, but what is considered his own culture, occasionally forgets that he is unwelcome among whites as soon as he steps off stage.

Soon, Frank and Dr. Shirley form an uneasy friendship as they cross the Deep South, discovering uncomfortable truths about each other, and eventually, themselves.

The first part of the movie takes place largely in Frank’s community -- full of stereotypical wiseguys and the kinds of Italian caricatures I guess the world has collectively decided are inoffensive. Even so, it comes as a surprise that the performance that Mortensen gives as Frank is quite so broad. But the real Vallelonga’s son, Nick, co-wrote the script with Farrelly and Bryan Hayes Currie, so one imagines that at the very least it’s faithful to who he was. Mortensen gives him a vibrancy and a humanity that makes his transformation into a more tolerant person feel incremental instead of a grand epiphany. As Shirley, meanwhile, Ali taps into a Sidney Poitier-like character type -- an exemplary and therefore “harmless” specimen of his race -- and finds the frustration, and powerfully, confusion roiling beneath that placid surface.

Shirley understands all too well what he must do in order to be able to play and enjoy the artistic freedom that his talent affords him, and understands the cost -- to his relationships, and to his very sense of identity. He aims to hold both he and Frank to that impossible standard, correcting his driver’s diction, demeanor, behavior and even his worldview, and Ali communicates how exhausting, and exasperating, maintaining that can be.

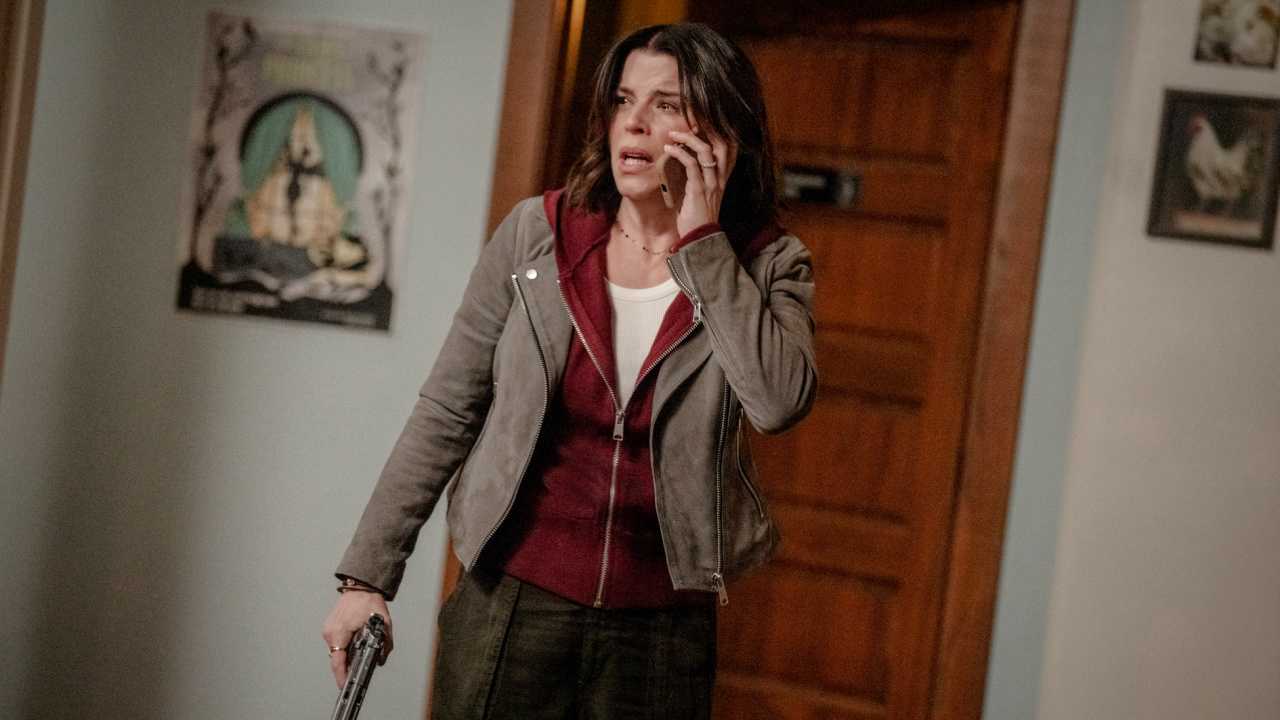

Conversely, and though the film seems to soften Frank’s racism (he always seems more frequently adjacent to the most offensive stuff instead of participating in it), he becomes a witness less to Shirley’s race than to his discipline, artistically and personally. He does so while still being able to enjoy the luxury of being a white man who can get into a scuffle or talk back to a mouthy jerk or even just ask for what Shirley has earned and deserves. “Dignity always prevails,” Shirley correctly observes, but Frank knows that it helps to fall back on the language of a tour rider -- or, in a clinch, a revolver hidden in his waistband.

Though they eventually narrow their view to one or two unlucky so-and-sos, Farrelly’s films are very often about families or large communities, and this one is the same -- and in particular, it’s about learning that the community in which we live is bigger than we think. Such realizations with regard to race are, certainly at this date, more than a little bit hokey, but this film can be forgiven for showcasing average whiteness learning some important lessons from black exceptionalism, especially with two incredibly gifted actors behind the wheel, steering us towards the better angels of our nature.

Ultimately, “Green Book” is maybe not a masterpiece, but it’s a master-class from two of our most talented actors. Most of all, it is a balm for times that seem determined to remain volatile, and often painful. It, like the many dozens of movies before it about the black-white relations of generations past, will not likely solve the problems of modern racism, but it’s still an important reminder that we can always learn new things about and from one another -- in which case, it’s a good idea to keep one’s mind, and heart, open.